This year in LLVM (2023)

This is my second year working on LLVM at Red Hat. Similar to last year’s blog post, I want to summarize some of the things I’ve worked on this year.

Opaque pointers

The opaque pointer migration is the main task I worked on last year, and it carried substantially over into this year as well.

The goal of this change was to replace typed pointers like i32*, void(i32)** or %struct.T* with a single opaque pointer type ptr. I’m not going to reiterate the full motivation behind the change here, but it basically comes down to simplifying the IR design, by removing a pervasive element that does not actually carry any semantic meaning.

Opaque pointers were enabled by default in LLVM 15, but typed pointer support was only removed one year later, in LLVM 17. In the meantime, we had to support both modes.

The reason for this is simple: Tests. We have tens of thousands of regression tests, and a large fraction of them were affected by the opaque pointer migration. Over the course of a year, I have ported well over fifteen thousand tests to opaque pointers.

This was supported by a healthy dose of automation, but unfortunately also required a significant amount of manual intervention, which is why it took so much time to complete this step.

The -no-opaque-pointers option was removed in July, which essentially marked the completion of the migration. The only remaining work (that is still ongoing) are code cleanups to remove no longer needed code, such as unnecessary pointer bitcasts.

I’m very happy that this migration is finally finished! But this just means that it’s time to start the next project…

ptradd

The natural followup to opaque pointers is to migrate away from out current type-based representation for pointer arithmetic. There are many redundant, but semantically equivalent, ways to encode the same operation:

%struct = type { i32, { i32, { [2 x i32] } } }

%ptr = getelementptr %struct, ptr %base, i64 1, i32 1, i32 1, i32 0, i64 1

%ptr = getelementptr i32, ptr %base, i64 7

%ptr = getelementptr i8, ptr %base, i64 28

This causes a lot of implementation complexity, missed optimization opportunities and compile-time overhead. The plan is to replace the type-based representation with an offset-based one, which matches the actual semantics of the operation:

%ptr = ptradd ptr %base, i64 28

While I have written an RFC on the topic, I’ve not made much implementation progress this year.

Based on feedback from the RFC, we will not be introducing a new instruction right away, and instead start by performing more canonicalization of getelementptr instructions. In particular, it should be noted that getelementptr i8 and ptradd are equivalent, so we can start by canonicalizing GEPs to use i8 as the element type.

The first change in this direction, which is canonicalization of constant offset GEPs, is ready and will land soon. This is a very important first step, and will already fix many optimization issues by itself.

Next steps after that will be to change the inrange representation, canonicalize constant expression GEPs, canonicalize variable index GEPs, and finally to disallow non-i8 GEPs (at which point we can just spell them ptradd). I hope to make significant progress on this next year.

Constant expression removal

Another project that carried over from last year is the removal of most constant expressions from LLVM. The goal of this project is to remove constant expressions that cannot be represented as relocations in common object formats, and represent them as ordinary instructions instead.

I’ve made good progress this year, removing the select, and, or, lshr, ashr, zext, sext, fptrunc, fpext, fptoui, fptosi, uitofp, and sitofp expressions. The only expressions still scheduled for removal are icmp, fcmp, mul, xor, extractelement, insertelement and shufflevector.

Of the remaining ones, getting rid of icmp is probably the most important, because it will at least make it technically possible to fix certain miscompiles in -fno-delete-null-pointer-checks mode (which depends on function attributes, while constant expressions are independent of the function, and even the module).

Metadata semantics changes

Undefined behavior in LLVM comes in two flavors: One of those is immediate undefined behavior, which basically works the same as in C, and poison values, which get propagated by most operations and only turn into immediate undefined behavior in certain contexts, for example when you try to branch on them.

We generally prefer using poison values over immediate undefined behavior whenever possible, because the former can be speculatively executed, while the latter can not.

The !nonnull, !range, and !align metadata for loads and calls used to be specified in terms of undefined behavior, which means that it had to be dropped during speculation. I have changed the semantics to make them return poison on violation instead.

In this case we get the best of both worlds, because poison-generating metadata like !range can be combined with !noundef to turn the resulting poison value into immediate undefined behavior. This is the representation that frontends would typically generate.

Then, during speculation, we can drop the !noundef metadata, while keeping the !range metadata. For example, in the following snippet we can retain the fact that %res is actually a boolean:

start:

br i1 %c, label %if, label %join

if:

%load = load i8, ptr %p, !range !{i8 0, i8 2}, !noundef !{}

br label %join

join:

%res = phi i8 [ %load, %if ], [ 0, %start ]

; Can fold to (assuming the load is speculatable):

start:

%load = load i8, ptr %p, !range !{i8 0, i8 2}

%res = select i1 %c, i8 %load, i8 0

Keeping this information around is especially relevant for languages like Rust, which tend to have a lot more information about value constraints than languages like C.

For this semantics change, the main tricky part was identifying and updating various transforms to correctly drop or combine metadata under the new semantics. In particular, many CSE/GVN style transforms were affected.

getelementptr inbounds

The inbounds flag on the getelementptr instruction indicates (if we gloss over a lot of detail) that the pointer arithmetic does not go outside an allocated object (where the pointer to the end of an object is still considered “inbounds”).

Historically, there was a special case that the offset 0 is considered inbounds of the null pointer, even though no allocated object may exist at that address (by default). This is necessary to satisfy C++ language semantics.

Now we generalize this by saying that offset 0 is always inbounds, regardless of what the base pointer is. This was a long-standing request from the Rust community, to ensure that operations on zero-sized objects at arbitrary addresses are always well-defined.

An additional benefit from this change is that we can now preserve inbounds during certain transforms that materialize zero-offset GEPs, such as the following:

%gep = getelementptr inbounds i8, ptr %p, i64 %offset

%sel = select i1 %c, ptr %gep, ptr %p

; Can fold to:

%sel = select i1 %c, i64 %offset, i64 0

%gep = getelementptr inbounds i8, ptr %p, i64 %sel

Previously we had to drop inbounds, leading to significant optimization regressions in some cases.

writable and dead_on_unwind

Consider the following Rust snippet:

pub fn new_from_uninit() -> Foo {

let mut x = std::mem::MaybeUninit::uninit();

unsafe {

init(x.as_mut_ptr());

x.assume_init()

}

}

This will currently create a stack allocation for x, call init on it, and then perform a memcpy to move the memory into the return slot. It would be much more efficient if we could call init() directly on the return slot and save the temporary stack allocation, as well as the copy.

LLVM’s “call slot optimization” is responsible for optimizing cases like this. However, in this case it fails, because the call to init() may unwind (panic). In that case, as far as LLVM knows, there would be an observable difference in behavior: The return slot would not be modified on unwind before the optimization, and would potentially be modified after.

Of course, we know that the return value will not actually be used if an unwind (panic) occurs, but we had no way to tell LLVM that this is the case.

To enable this optimization, I’ve added two new parameter attributes. The first one is writable, which indicates that it’s legal to introduce stores to the parameter. This both excludes read-only memory, as well as memory for which introducing a store would result in a data race. The transform was previously incorrectly applied in cases where this could not be guaranteed.

The second one is dead_on_unwind, which indicates that the parameter will not be read after an unwind occurs. Both attributes together (plus a long list of other preconditions) enable the desired transform, once the frontend starts emitting them.

zext nneg

LLVM generally prefers unsigned operations over signed ones, as they tend to optimize better. For that reason, we perform a number of canonicalizations from signed to unsigned if the operations are actually equivalent.

For example, we replace sign extension (sext) with zero extension (zext) if the operand is non-negative. We also do the same for arithmetic shift right (ashr) to logical shift right (lshr), and for integer comparisons (signed predicate to unsigned predicate).

However, this is not always beneficial. For example, if a value is used in a signed context (like a signed comparison), then a sign extend may optimize better. There are also some weird architectures like RISC-V that have a preference for sign extensions.

It is sometimes possible to undo the canonicalization if necessary, but this is unreliable, because information may have been lost, or there is an impedance mismatch in analysis capabilities.

The zext nneg flag addresses this, by retaining the fact the operand is non-negative. This makes it easy to treat the zext nneg as a sext when profitable.

or disjoint

The or disjoint flagaddresses another, very similar problem: We canonicalize add instructions a + b to a | b, if a and b have no common bits (in which case all of add, or and xor are equivalent).

Once again, this is not universally profitable. While it allows various bitwise optimizations to apply, we also lose optimizations that operate on additions. For example, many targets have addressing modes that incorporate an offset, while a bitwise or contributing to an address generally needs to be materialized as a separate instruction.

The or disjoint flag retains the information that the bits are disjoint, and makes it trivial to convert it back into an add, if it is found to be beneficial.

I didn’t add this flag myself (Craig Topper worked on the implementation), but did a lot of the related bringup work (fixing miscompilations it introduces and using it in various transforms).

Future work: More flags

While zext nneg and or disjoint are a good start, I think this is an area that would benefit from further work. A number of additional cases where we could preserve information during canonicalization are:

lshr nnegwhen canonicalizingashrwith non-negative LHS. This has come up as an issue a few times, but possibly not often enough to justify the flag yet.icmpsigned to unsigned predicate canonicalization. This one can be applied when either both operands are non-negative, or both are negative, so annnegflag isn’t quite the right model here. A possible way to handle this would be support sign-agnostic predicates likeicmp lt, which produce a poison value if theultandsltresult differs. I think that solving this problem would definitely be worthwhile, as not retaining this information can cause severe regressions (e.g. due to failure to eliminate conditional branches).trunc nuwandtrunc nswto indicate that the truncated bits are all zero or all signs. For example, when induction variable (IV) widening is performed, we know that all truncated users will be one of these, but the information is easily lost, and we end up inserting unnecessary masking operations.

Compile-time improvements

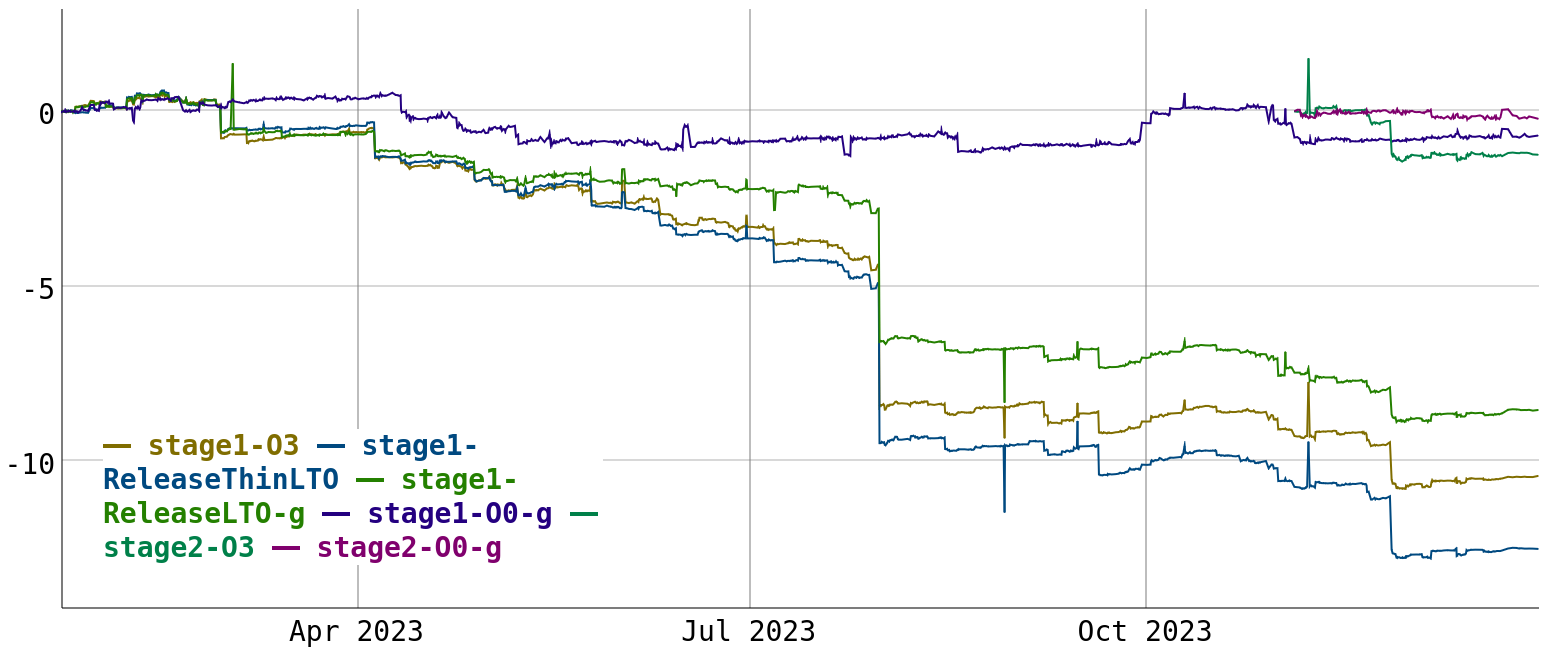

Unlike the last, this year has been quite good for compile-times. The compile-time changes since 2023-01-22 are plotted in the following graph. It shows the percentual improvement in the “instructions retired” metric for the geomean of all CTMark benchmarks.

I have cut off the start of January due to a change in server configuration, which would make the results misleading.

Overall, we see improvements in the 8-12% range for optimized builds, while unoptimized builds only improve marginally. In the following, I’ll go through some of the more significant improvements I have made.

The largest improvement of 4-5% comes from making InstCombine use a single-iteration, instead of trying to reach a fix-point. See that blog post for a detailed discussion of this change.

I have made a series of improvements to semi-NCA (part of dominator tree construction), starting with reducing hash table lookups. These changes add up to more than 1% improvement. I think there is still some more room for improvement here, especially around DFS walks.

We get a 0.7% improvement from removing a fold from CorrelatedValuePropagation, which other existing transforms perfom much more efficiently.

Not calculating BlockFrequencyInfo (BFI) in various passes for non-PGO builds gives a 0.7% improvement. The calculated BFI is not actually used in this case.

Switching loop-invariant code motion (LICM) to not require optimized MemorySSA gives a 0.9% improvement. Instead, we lazily optimize the small subset of memory uses we’re interested in. Arthur Eubanks later won another 0.5% by doing the same for DSE.

One of my GSoC students this year also worked on compile-time improvements. Read the report for all the details, but here are a couple of highlights from their work:

Moving alignment inference from InstCombine into a dedicated pass gives a 0.6% improvement. This is mainly because the pass is run less often than InstCombine.

Optimizing pruning worklist population in DAGCombine gives a 0.5% improvement. Just adding things to a worklist can be quite expensive!

Optimizing the SetVector data structure gives a 0.4% improvement. This uses a linear scan instead of a hashtable lookup when the SetVector is in “small” mode, similar to what we already did for SmallPtrSet.

Finally, I have also made a number of improvements to the compile-time tracking infrastructure. I’ve migrated the runner from an AX41 to an AX52 server, which is a good bit faster. This new time budget is used to perform a two-stage clang build.

The new procedure looks like this:

- Build stage1 clang using host gcc and ccache. This will be fast for most commits thanks to ccache.

- Build stage2 clang using stage1 clang and ThinLTO. Collect wall-time timings from ninja log and instrument each compiler/linker invocation to get

instructions:udata. Also collect file sizes. - Build CTMark in O3, ReleaseThinLTO, ReleaseLTO-g and O0-g configuration using stage1 clang.

- Build CTMark in O3 and O0-g configuration using stage2 clang.

This gives us a number of new data points:

- We get compile-time coverage for a project (clang) that is much, much larger than anything in CTMark. Though from the data I have to date, it seems like CTMark is actually more representative than I would have guessed.

- We can catch regressions to clang build time unrelated to optimizer changes. I’ve caught a few instances of significant build time regressions due to includes being (unnecessarily) added to core LLVM headers.

- We can catch optimization regressions that affect clang itself (which manifest by regressing the stage2 CTMark builds only). This doesn’t seem to be common.

- We can see the different effect of changes on a gcc-built and a clang-built compiler. It happens sometimes that a change gives a large improvement for the gcc-built stage1 compiler, but makes little difference for the clang-built stage2 compiler, or vice versa.

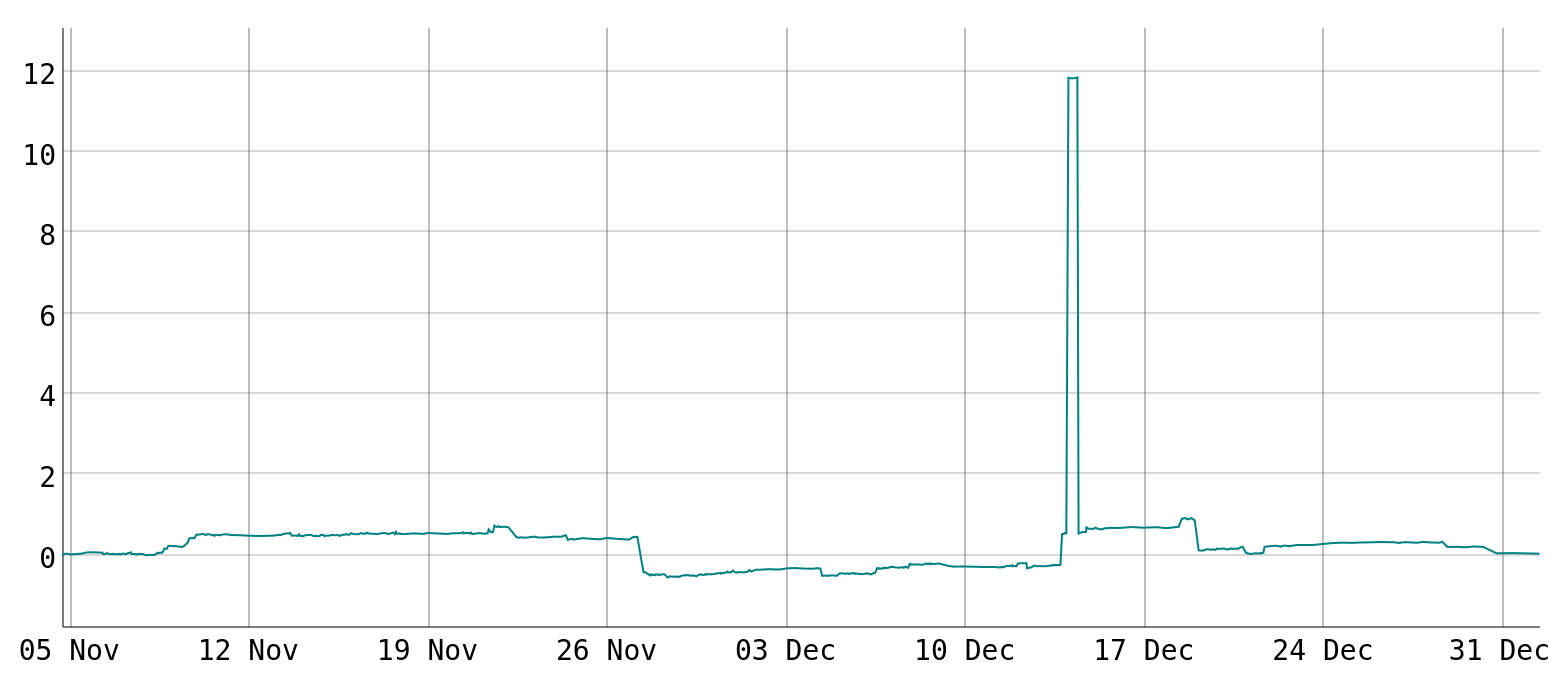

The following graph shows the compile-time of stage2 clang (in percent since start using the instructions:u metric) since I started collecting data:

If you’re wondering what’s up with that 10% spike, this was a huge compile-time regression to a single file, caused by some large generated functions being added.

Optimization improvements

I don’t do much work on optimization improvements, if they don’t require changes to IR design or substantial infrastructure changes. We have a lot of people who want to contribute new optimizations, and our bottleneck is in getting them reviewed, so that’s what I tend to focus on.

I think all of the more interesting optimizations I worked on this year were related to conditions in some way. Some examples:

- Performing optimizations based on dominating KnownBits conditions. For example, if we have a condition like

if (x & 1 == 0)then we can optimize based on the fact that the low bit ofxmust be zero. This is based on a new DomConditionCache, and comes at some compile-time cost. - Performing range-based optimization based on conditions known at the use-site. In particular, this enables range-based optimization of instructions used only inside a

selectbased on the select condition. This is a partial solution to a general problem that still requires further work. - Perform optimizations of ands/ors using equality conditions by trying to perform simplification with replaced operands. This is interesting in that this generic fold ended up subsuming a large number of existing hand-written folds. I always love it when that happens.

Zero-length operations on null

Together with Aaron Ballman, I have been working on a proposal for the C standard, to make “zero length” operations on null pointers well defined. In particular:

NULL + 0becomes well-defined and returnsNULL.NULL - NULLbecomes well-defined and returns0.memcpy(NULL, NULL, 0)becomes well-defined and does nothing. Similar for other library calls.

The original proposal was targeted at library functions only, and additionally made memcpy(p, p, n) well-defined, which is something that all major C compilers already rely on. Based on feedback, I ended up switching the proposal to focus on various NULL + zero length cases instead.

This will bring C semantics more in line with C++ semantics, and put use of libc as a builtin provider for languages like Rust on a more stable footing.

Rust

As usual, I carried out the upgrades to LLVM 16 and later LLVM 17 in Rust.

The LLVM 16 upgrade was more painful than usual. Early on, we hit a bolt instrumentation miscompile, which manifested in our most complex build configuration (a sequence of multiple rebuilds of libLLVM and rustc with various PGO settings) and thus took quite a while to track down.

After the upgrade landed, it completely broke CI due to a bad interaction with the download-ci-llvm feature. The problem was that LLVM 16 started using C++ 17, but did not require a GCC version that has a stable C++ 17 ABI, and the std::optional ABI did indeed change between libstdc++ 7 and 8.

We “fixed” this by making sure all our builders use at least GCC 8, but this is probably something we should take into account the next time LLVM raises its host compiler requirements. We should not consider a compiler version “supported” if it still uses an experimental ABI for the used C++ version.

One of my GSoC students this year worked on Rust-related optimizations in LLVM. Read the report for all the details, but I think that most interesting/important optimizations are related to removal of memcpy’s in additional situations.

One of these is about removing memcpy’s before function calls where the argument is known immutable, so there is no need to copy it into a temporary stack slot. The second is the so-called “stack move” optimization, where a memcpy between two stack slots can be removed by merging the slots into one.

A number of the topics covered above (metadata semantics change, getelementptr inbounds, dead_on_unwind) are at least partially motivated by Rust needs. Some other things I worked on are:

- Bringing the change to allow inlining of drop calls in landing pads over the finishing line. This was blocked on a stack coloring bug affecting Windows exception handling. This has firmly reinforced that Windows exception handling is “batshit insane” in my mind.

- Do preparatory work to allow us to change the alignment of i128 on x86 to 16 bytes, to match the SystemV ABI. The alignment of i128 was changed in LLVM 18, but we also need to get this working on older LLVM versions, by making sure we don’t rely on LLVM’s own layout calculations.

RHEL

This is the first year I actually did some direct work on the product we’re selling, namely Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

We ship LLVM via the LLVM toolset, which gets updated to the next LLVM version with each minor RHEL release. Due to the way the release cycles of LLVM and RHEL align, it tends to be one version behind the latest one.

LLVM updates happen in Fedora first. Then, we mostly copy over the changes to CentOS Stream, which then get merged into RHEL by automation and go through QE there.

Relative to Fedora, there are mostly some workarounds due to a different build environment (e.g. packages not being available or old), as well as integration with the GCC toolset, which provides up-to-date versions of GCC, binutils, etc.

This year, I performed the update to LLVM 16 for RHEL 9.3 and LLVM 17 for RHEL 8.10 (not released yet).

As part of the RHEL 9 work, I also switched our LLVM packages to be built with clang and ThinLTO, just like we do on Fedora. This turned out to be more complex than anticipated, due to various issues related to too old system binutils/gdb/etc versions.

Other

I attended my first EuroLLVM conference this year, and gave a talk there: A whirlwind tour of the LLVM optimizer. It provides an overview of LLVM’s middle-end optimizer.

The conference was great and quite productive as far as discussions were concerned. The presentations were unfortunately heavily skewed towards MLIR content, which I don’t particularly care for.

I have spent a lot of time this year on code review. Especially after Sanjay Patel stopped working on LLVM, it feels like I’m the primary reviewer for most of the LLVM middle-end.

I don’t have good statistics on this (especially with Phabricator being decomissioned), but based on a back of the envelope calculation, I probably reviewed something like 1500 patches this year.

Despite that, the review backlog is always increasing, so some patches invariably end up in review limbo…